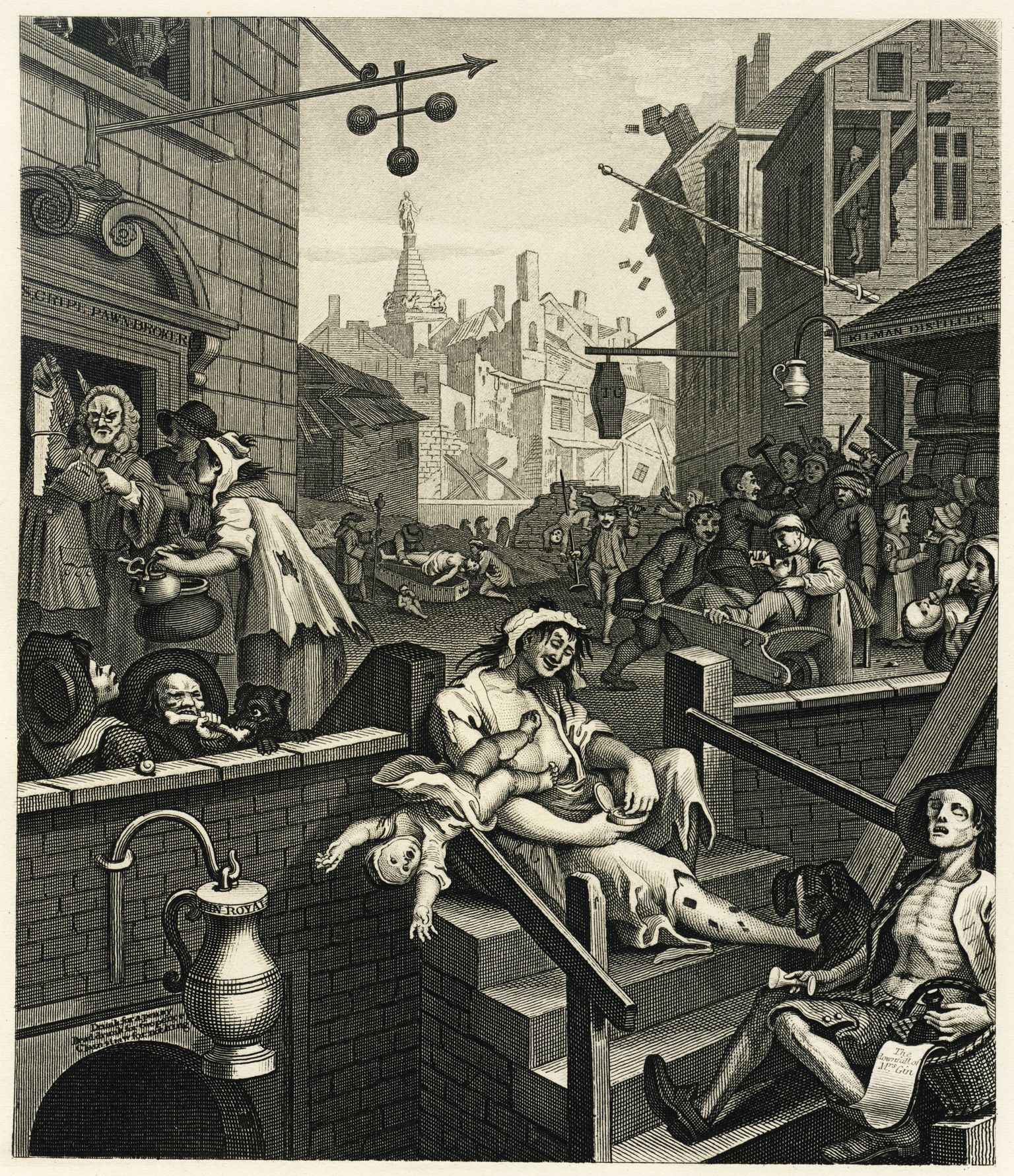

William Hogarth’s 1750s Gin Lane does not paint the juniper-based spirit in a particularly positive light.

His depiction of London life, gripped by a crippling gin craze with roots dating 20 years earlier when Dutch king William of Orange, not long after he had taken the throne, lifted laws on distillation.

The consequences were dire. By the end of the 1720s, 75% of children under five were dying, the death rate had exceeded births and any efforts at sexy time were being thwarted by impotence – inducing alcohol.

By the 1730s men, women and children (yes, children) were guzzling two pints of gin a week. Gin’s pseudonyms alone tell the story of how degenerative this liquid was viewed-‘busthead’, ‘crank’, ‘strip-me-down-naked’, ‘blue ruin’, ‘strikefire’…. hardly discerning monikers.

The battered masses were making bad life decisions and newspapers lapped up the misery, but one sob story really tickled the tabloids. In 1734 a poverty stricken, gin addicted Judith Defour murdered her baby and exchanged the infant’s clothes for money to buy booze.

The shocking crime and its subsequent trial coverage became a fulcrum for attempts at distillation reform, but government efforts fell on gin drowned ears and by the 1740s 11 million gallons of the spirit was being distilled in London.

The government was desperateby 1751 seven Gin Acts had failed and the last throw of the dice, as so often is the case in national dire straits, was to focus on a drawing.

Up stepped the doyen of satirical sketches, William Hogarth.

Hogarth’s Gin Lane made an immediate impact, shining a sobering light on the consumption of the spirit.

In the piece, Madame Genever – or Judith Defour – dominates, ginned up to her eyeballs as she lobs her baby* into the doorway of a gin shop.

Behind her, a coffin is being filled with another woman who had died from drinking too much gin. Her child watches on, while sipping gin.

To the right of the image, a woman adopts a seemingly caring cuddle with her baby – but look closer and you’ll see that she is force-feeding her child gin. You shouldn’t give a baby gin.

Top right. There’s a guy hanging from the rafters. Why? Gin.

There’s a chap in the bottom corner who looks emaciated, possibly dead, but has a very fancy gin Martini glass on him, and his dog looks sad because all the gin has run out. Has he run out of doggy gin? Probably.

There’s also a chap who looks like an olden-day hipster – moustache, bellows, that kind of thing. He is drunk on gin and has speared a baby. What point is Hogarth trying to make here? If you drink gin, he suggests, you may spear a baby. Spearing babies, even back then, was not allowed.

Buildings crumble because all the workmen back then had replaced a lovely cuppa splosh with a big glass of gin, the economy is in a right state because everyone’s spent money on gin and nothing else, riots erupt, starvation ensues and London is gin-soaked and not a nice place to be.

But, while we can all agree children guzzling gin is bad news, Hogarth’s satirical sketch had a deeper meaning. Gin takes the blame for London’s downfall, and certainly it deserves some – if only Londoners could’ve drunk less, but better?

But Hogarth was identifying a brutal poverty behind the public’s thirst for gin – and it’s alluring chaser of escapism. Aggressive urbanisation and lack of space in London led to the rapid spread of disease, while prostitution, unemployment and neglect of children were commonplace.

The pressures on London society were unprecedented, inequality was driving citizens to drink and the government were guilty of allowing too much of both.

*N.B Hogarth was hopeless at drawing babies, it’s massively out of proportion with the rest of the painting.